This is shocking, really, because I've certainly been reading stuff, and not just heavily illustrated books about fire engines either.

All the more so recently, in fact, because I got a Kindle for my birthday. It turns out many of the habits I've picked up over years of reading paper books don't transfer to electronic devices, so that it's actually much quicker for me to read the same amount of text on a screen than it would be bound between two covers. (This despite the fact that a Kindle display is black-on-white, unbacklit and -- apart from the technological framing device -- pretty much indistinguishable from reading something on the page anyway.)

All the more so recently, in fact, because I got a Kindle for my birthday. It turns out many of the habits I've picked up over years of reading paper books don't transfer to electronic devices, so that it's actually much quicker for me to read the same amount of text on a screen than it would be bound between two covers. (This despite the fact that a Kindle display is black-on-white, unbacklit and -- apart from the technological framing device -- pretty much indistinguishable from reading something on the page anyway.) Reviewing everything in depth that I've read in the past six months (even if I could remember all of it, which I suspect I can't) would take a terribly long time, and probably be boring to read. So I'll give a few one-paragraph reviews of the more interesting stuff, and then head into Twitteresque one-liner territory for brief responses to the others.

(NB: All links in this post are to paperback editions of the books in question, regardless of the format I read them in. If you'd prefer me to start linking to the Kindle versions, do let me know.)

I thgought China Miéville's Embassytown was great -- cerebral SF of what we might now call "the old school", the New Wave tradition of the '60s and '70s with its interest in anthropology and politics and its worthy literary aspirations. Intriguingly for the Marxist Miéville, it's a recapitulation of the biblical Fall myth among other things, though mostly it reads as a homage to Ursula le Guin, who reviewed it in glowing terms in The Guardian. It's not flawless -- the protagonist is blurry, and the depiction of the disintegration of the titular society too protracted, going through supposedly distinct but actually very vague stages, rather as if working from a sociology textbook for post-apocalyptic societies. Overall, though, it's engrossing and ingenious.

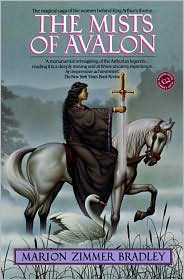

I thgought China Miéville's Embassytown was great -- cerebral SF of what we might now call "the old school", the New Wave tradition of the '60s and '70s with its interest in anthropology and politics and its worthy literary aspirations. Intriguingly for the Marxist Miéville, it's a recapitulation of the biblical Fall myth among other things, though mostly it reads as a homage to Ursula le Guin, who reviewed it in glowing terms in The Guardian. It's not flawless -- the protagonist is blurry, and the depiction of the disintegration of the titular society too protracted, going through supposedly distinct but actually very vague stages, rather as if working from a sociology textbook for post-apocalyptic societies. Overall, though, it's engrossing and ingenious.  Among the many, many books which it's scandalous I never read before reaching adulthood, let alone middle age (I'm on Dune at the moment), is The Mists of Avalon by Marion Zimmer Bradley. I'd always understood that this was an epic feminist reworking of the Arthurian saga, and it's certainly true that using solely female characters for viewpoint[1] gives an interestingly skewed perspective on the tradition. However... the opening hundred or so pages (the novel is, dauntingly, 1009 pages plus an unnumbered prologue in length) are entirely structured around which of two men Arthur's mother Igraine fancies, with much wittering on about ancient reincarnated souls from Atlantis, and it doesn't get a great deal better. Morgaine is by far the most interesting character, and even she's obsessed with Lancelot, Arthur and later Accolon. It's possible that the female characters' preoccupation with romance is meant to be making a feminist point about their role in such societies, but overall the book reads like a shambling hybrid of sword-and-sorcery and Mills-and-Boon. It does get better, picking up particularly with the political intrigues of the final quarter... but it's quite a slog, and not a rewarding one.

Among the many, many books which it's scandalous I never read before reaching adulthood, let alone middle age (I'm on Dune at the moment), is The Mists of Avalon by Marion Zimmer Bradley. I'd always understood that this was an epic feminist reworking of the Arthurian saga, and it's certainly true that using solely female characters for viewpoint[1] gives an interestingly skewed perspective on the tradition. However... the opening hundred or so pages (the novel is, dauntingly, 1009 pages plus an unnumbered prologue in length) are entirely structured around which of two men Arthur's mother Igraine fancies, with much wittering on about ancient reincarnated souls from Atlantis, and it doesn't get a great deal better. Morgaine is by far the most interesting character, and even she's obsessed with Lancelot, Arthur and later Accolon. It's possible that the female characters' preoccupation with romance is meant to be making a feminist point about their role in such societies, but overall the book reads like a shambling hybrid of sword-and-sorcery and Mills-and-Boon. It does get better, picking up particularly with the political intrigues of the final quarter... but it's quite a slog, and not a rewarding one. (Which reminds me, ask me about Dune in a few week's time.)

Another I'm ashamed of not having read before is Richard Matheson's I Am Legend, a seminal reinvention of the vampire myth whose influence in the media of the late 20th and early 21st centuries is as visible as that of Dracula[2]. It's a powerful exploration of loneliness and paranoia, but its revolutionary nature lies in its insistence on treating vampirism as a rational phenomenon, suseceptible to analysis through microscopes and epidemiology. It's a short read (I polished it off in a couple of evenings) but a compelling and impressively scary one.

Another I'm ashamed of not having read before is Richard Matheson's I Am Legend, a seminal reinvention of the vampire myth whose influence in the media of the late 20th and early 21st centuries is as visible as that of Dracula[2]. It's a powerful exploration of loneliness and paranoia, but its revolutionary nature lies in its insistence on treating vampirism as a rational phenomenon, suseceptible to analysis through microscopes and epidemiology. It's a short read (I polished it off in a couple of evenings) but a compelling and impressively scary one. Jill Paton Walsh's latest continuation of Dorothy L. Sayers's sublime Lord Peter Wimsey series, The Attenbury Emeralds, is a slight thing with a needlessly convoluted plot (not unlike Sayers' own Five Red Herrings, which is my personal least favourite of her works).

The device of having the first half of the book consist of a lengthy flashback narrated in dialogue by Lord Peter and his manservant Bunter is weirdly alienating at first, but one gets used to it. The detective story itself is uninvolving in any case, the real joy of the book being the author's unashamedly fannish enjoyment of the characters, whose continuing lives are lovingly recounted. There's a particular turn of events near the novel's end which changes the status quo entirely in a way which few sequelists-of-other-authors would have dared. I've read reviews which suggest that these scenes also bear some interesting thematic freight, but on the whole the book has nothing of the depth of Sayers' more cerebral and sophisticated works.

The device of having the first half of the book consist of a lengthy flashback narrated in dialogue by Lord Peter and his manservant Bunter is weirdly alienating at first, but one gets used to it. The detective story itself is uninvolving in any case, the real joy of the book being the author's unashamedly fannish enjoyment of the characters, whose continuing lives are lovingly recounted. There's a particular turn of events near the novel's end which changes the status quo entirely in a way which few sequelists-of-other-authors would have dared. I've read reviews which suggest that these scenes also bear some interesting thematic freight, but on the whole the book has nothing of the depth of Sayers' more cerebral and sophisticated works. The Islanders by Christopher Priest is a fascinating example of the "novel written as reference book" genre --

in this case, a guidebook to the Dream Archipelago, the setting of his earlier novel The Affirmation and a number of short stories. Like The Dictionary of the Khazars or The, ahem, Book of the War, the book constructs overarching stories across its multiple entries, with various strands (the lives of certain artists, a murder mystery) linking up in sundry ways at multiple points in the non-narrative. More than either of those, however, this book renders these links problematic and difficult, to the extent that any attempt to tease out a definitive "truth" founders in the gaps between the entries[3]. The book makes much of the Archipelago's inconsistent, or at least unfathomable geography, and the difficulty of navigating a straight course between these island-entries may be designed to mirror that. I decided long ago that trying to get them to make literal sense was not the best way to enjoy Priest's books, and with that proviso this is a fascinating book, often beautifully written.

in this case, a guidebook to the Dream Archipelago, the setting of his earlier novel The Affirmation and a number of short stories. Like The Dictionary of the Khazars or The, ahem, Book of the War, the book constructs overarching stories across its multiple entries, with various strands (the lives of certain artists, a murder mystery) linking up in sundry ways at multiple points in the non-narrative. More than either of those, however, this book renders these links problematic and difficult, to the extent that any attempt to tease out a definitive "truth" founders in the gaps between the entries[3]. The book makes much of the Archipelago's inconsistent, or at least unfathomable geography, and the difficulty of navigating a straight course between these island-entries may be designed to mirror that. I decided long ago that trying to get them to make literal sense was not the best way to enjoy Priest's books, and with that proviso this is a fascinating book, often beautifully written.  The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo I thought was pretty poor -- apart from some attention-grabbing (but quite distasteful) violence, it had very little to recommend it. It's badly structured, with dull prose (in which people constantly note the dimensions and contents of the rooms they're in as if already planning a film set) and an apparent belief that corporate accountancy fraud is thrilling in itself. I've read worse bestsellers, but not ones I'd been led to believe were actually good.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo I thought was pretty poor -- apart from some attention-grabbing (but quite distasteful) violence, it had very little to recommend it. It's badly structured, with dull prose (in which people constantly note the dimensions and contents of the rooms they're in as if already planning a film set) and an apparent belief that corporate accountancy fraud is thrilling in itself. I've read worse bestsellers, but not ones I'd been led to believe were actually good. OK, time to speed up.

Flashman was enormous fun -- the trick of making its anti-hero appealing is to give him absolutely no illusions about his own despicableness. I'll definitely be seeking out the further volumes, to further my knowledge of nineteenth-century military history as well as to enjoy the often hilarious writing.

Simon Armitage's verse translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is very enjoyable, too -- a sympathetic and populist modernisation of a poem whose chief barrier to accessibility is its language.

Michelle Paver's Dark Matter is a frankly terrifying story about a haunted Arctic expedition, and one man who finds himself alone in the perpetual night with a pack of huskies and an angry ghost. One for reading in the daytime, preferably in company.

Michelle Paver's Dark Matter is a frankly terrifying story about a haunted Arctic expedition, and one man who finds himself alone in the perpetual night with a pack of huskies and an angry ghost. One for reading in the daytime, preferably in company. Bad Things is Michael Marshall Smith by the numbers -- perfectly-paced storytelling with entertaining prose, but ultimately with nothing new to say. Think "Blair Wicker Man Project", and you essentially don't need to read the novel.

Terry Pratchett's Snuff is terribly disappointing, at least by the standards of previous City Watch books (because, let's face it, the Discworld series as a whole has always been hit-and-miss). In the light of his well-publicised medical condition, it's difficult not to see this as Pratchett losing his touch altogether, but I'm hoping it's a blip.

To end on a happier note, David "not that one" Mitchell's The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet is excellent -- a fascinating story of European contact with the isolationist Japan of the 1790s, dealing sympathetically with both Japanese and Dutch culture (though somewhat less sympathetic to the English when they turn up), and tinged round the edges with smudges of the fantastic. It's well worth a read.

To end on a happier note, David "not that one" Mitchell's The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet is excellent -- a fascinating story of European contact with the isolationist Japan of the 1790s, dealing sympathetically with both Japanese and Dutch culture (though somewhat less sympathetic to the English when they turn up), and tinged round the edges with smudges of the fantastic. It's well worth a read. [1] Well, nearly. In fact, there's half a page (p981 in my edition) which is written from Mordred's point of view. In all I counted seven female viewpoint characters -- Igraine, Morgaine, Vivane, Gwenhwyfar, Morgause, Niniane and Elaine -- which is three more than most reviewers seem to mention.

[2] I certainly should have read it before writing The Vampire Curse, which covers some of the same ground. Oops.

[3] On the most obvious level, one character who is, according to the narrative, dead long before the guidebook is written, also supplies its Preface.