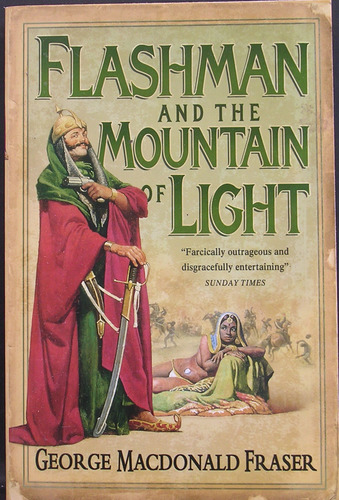

Since January I've read a further seven and a bit of George MacDonald Fraser's Flashman books, bringing me (in publication order) up to about quarter of the way through Flashman and the Mountain of Light. I'm enjoying them hugely, though I've found it improves them to intersperse them with other things. I'll blog about all twelve once I'm finished, I think.

Since January I've read a further seven and a bit of George MacDonald Fraser's Flashman books, bringing me (in publication order) up to about quarter of the way through Flashman and the Mountain of Light. I'm enjoying them hugely, though I've found it improves them to intersperse them with other things. I'll blog about all twelve once I'm finished, I think.  I believe I'd already read Michael Chabon's Manhood for Amateurs when I blogged that last piece, but it managed to slip my mind. It's a series of memoir-essays, rather than the handbook which the title promises for navigating masculinity, fatherhood and husbanddom in a post-feminist world (a shame, as I could really have done with one of those). It's very sweet though, and beautifully written, especially when talking about familiar elements of geekdom such as Lego and Doctor Who (Chabon is, inevitably, a fan). The only downside, and it's an equally characteristic one, is that it sometimes becomes doubly impenetrable by talking not only about sport but specifically about American sports.

I believe I'd already read Michael Chabon's Manhood for Amateurs when I blogged that last piece, but it managed to slip my mind. It's a series of memoir-essays, rather than the handbook which the title promises for navigating masculinity, fatherhood and husbanddom in a post-feminist world (a shame, as I could really have done with one of those). It's very sweet though, and beautifully written, especially when talking about familiar elements of geekdom such as Lego and Doctor Who (Chabon is, inevitably, a fan). The only downside, and it's an equally characteristic one, is that it sometimes becomes doubly impenetrable by talking not only about sport but specifically about American sports.  Frank Herbert's Dune is... well, long, isn't it? And there's an awful lot of it that's primarily about sand. To tell the truth, I was disappointed in this, one of SF's undoubted towering classics which I'd never quite got round to reading before. The worldbuilding is astonishing -- possibly unmatched outside Tolkein, in fact -- but most of it is kept off the page, in oblique hints in the appendices and glossary or at most in the dialogue of subplots which only temporarily diverge from the grand epic scenes of trudging on and on through some more sand. In fact, one gets a much, much stronger sense of Herbert's remarkable universe through watching David Lynch's magnificent film than by reading the book.Creating the Imperium but setting your story on Arrakis makes about as much sense to me as imagining the whole of Middle-Earth, then writing a huge novel set entirely in Forodwaith.

Frank Herbert's Dune is... well, long, isn't it? And there's an awful lot of it that's primarily about sand. To tell the truth, I was disappointed in this, one of SF's undoubted towering classics which I'd never quite got round to reading before. The worldbuilding is astonishing -- possibly unmatched outside Tolkein, in fact -- but most of it is kept off the page, in oblique hints in the appendices and glossary or at most in the dialogue of subplots which only temporarily diverge from the grand epic scenes of trudging on and on through some more sand. In fact, one gets a much, much stronger sense of Herbert's remarkable universe through watching David Lynch's magnificent film than by reading the book.Creating the Imperium but setting your story on Arrakis makes about as much sense to me as imagining the whole of Middle-Earth, then writing a huge novel set entirely in Forodwaith.The writing isn't particularly impressive either, often aiming for a grandeur which it never quite lives up to, and getting lost in its own abstractions. I was amused by the fleeting mention of a Fremen warrior called Geoff. I reckon he deserves his own web comic.

Another SF book failing for me to live up to its (more recent) hype was Lavie Tidhar's Osama, a poetic but ultimately rather predictable alternative-world fantasy with a Dickian twist. It gains kudos for dealing directly with the eponymous bogeyman of our age, who in a world free of terrorism has become the hero of a series of pulp thrillers whose author the protagonist, an equally Dickian private eye, must track down. The twist will not surprise anybody who's been keeping their eye on popular BBC time-travel series over the past few years, though, and ultimately I was left with the impression of a book which thinks itself cleverer and more daring than it is.

Another SF book failing for me to live up to its (more recent) hype was Lavie Tidhar's Osama, a poetic but ultimately rather predictable alternative-world fantasy with a Dickian twist. It gains kudos for dealing directly with the eponymous bogeyman of our age, who in a world free of terrorism has become the hero of a series of pulp thrillers whose author the protagonist, an equally Dickian private eye, must track down. The twist will not surprise anybody who's been keeping their eye on popular BBC time-travel series over the past few years, though, and ultimately I was left with the impression of a book which thinks itself cleverer and more daring than it is.

I read SJ Parris's Heresy as research for a thing I can't talk about yet, and found it distinctly under par. It's a mystery set in Elizabethan Oxford, where a serial killer's carrying out murders modelled on Foxe's Book of Martyrs, but is hugely less fun than that makes it sound. The formulaic plot relies on intelligent people being dense and making stupid decisions, and there's only the most desultory of attempts to help the reader inside the renaissance mindset. (To give you some idea, one character uses the word "paranoid" -- a solecism which this reviewer makes a valiant, but ultimately bollocks, effort to justify.)

Stonemouth, like Iain Banks' last non-genre novel, The Steep Approach to Garbadale, reads like a greatest hits collection: a family of gangsters; a young protagonist returning home; his long-lost love; violence, drugs and shagging; landscape and buildings; the merest hint of incest; a suspension bridge... Banks effortlessly gets inside the head of a generation for whom the internet and mobile phones have literally been around all their lives, in a way I'm not confident I could do at nearly 20 years younger. It's a good read -- fun, and evocative, and ultimately touching -- but don't expect any of the exuberant originality which makes Banks' truly great works great.

From Obverse Books this year I've read the latest Iris Wildthyme collection, Wildthyme in Purple, whose theme of pulp fiction leads to some surprising approaches, verging from pastiche to metafiction to massivel multitextual crossover; The Diamond Lens (Obverse Quarterly volume 1.3), which reprints some fascinating and genuinely excellent SF and fantasy short stories by the almost entirely neglected Fitz-James O'Brien; and Zenith Lives! (OQ volume 1.4), which revives the Sexton Blake villain Monsieur Zenith the Albino, in assorted tales by some familiar Obverse hands and -- in a startling coup -- Michael Moorcock.

From Obverse Books this year I've read the latest Iris Wildthyme collection, Wildthyme in Purple, whose theme of pulp fiction leads to some surprising approaches, verging from pastiche to metafiction to massivel multitextual crossover; The Diamond Lens (Obverse Quarterly volume 1.3), which reprints some fascinating and genuinely excellent SF and fantasy short stories by the almost entirely neglected Fitz-James O'Brien; and Zenith Lives! (OQ volume 1.4), which revives the Sexton Blake villain Monsieur Zenith the Albino, in assorted tales by some familiar Obverse hands and -- in a startling coup -- Michael Moorcock.In theory, Shada, Gareth Roberts' novelisation of Douglas Adams' unfinished Doctor Who story, combines two of my favourite things. In practice, the story is so familiar from partial releases including a scriptbook that it's rather less exciting than the combination would suggest. That said, it's not at all bad -- veteran Who novelist and latterly scriptwriter Roberts is doing his best (which can be pretty good) to do justice to something written by a genius on an off-day (which is also, mostly, good). He does a lot of work to firm up the characters and tidy the wobbly plot, explaining in an afterword that he was working with later versions of the script than have previously been published (so it's difficult to know what exactly he added, except when it's obviously novelistic). He also talks about a process of archaeologically extracting Adams' pre-deadline intentions from early drafts, abandoned plotlines and unfollowed hints, and again it's impossible to know how accurate his guesses are.

The book's not entirely satisfying: it's obviously not a pure transcription of the nonexistent TV story, but it's too tied to those roots to take flight as a novel. I enjoyed it, though.

Last year I read Terry Pratchett's The Wee Free Men and A Hat Full of Sky, and earlier this year I finished off the Tiffany Aching sequence with Wintersmith and I Shall Wear Midnight. They're very good books, full of humanity and realism (witchcraft is a painful, thankless path of discipline and service, and if you take pleasure in it, it probably means you've turned evil). If I had to quibble, I'd say that the wonderfully-drawn character of Tiffany becomes slightly less interesting as she leaves adolescence for womanhood, although this may be because the fourth book, Pratchett's penultimate to date, lacks focus in rather the same way as his more recent and disappointing Snuff.

Last year I read Terry Pratchett's The Wee Free Men and A Hat Full of Sky, and earlier this year I finished off the Tiffany Aching sequence with Wintersmith and I Shall Wear Midnight. They're very good books, full of humanity and realism (witchcraft is a painful, thankless path of discipline and service, and if you take pleasure in it, it probably means you've turned evil). If I had to quibble, I'd say that the wonderfully-drawn character of Tiffany becomes slightly less interesting as she leaves adolescence for womanhood, although this may be because the fourth book, Pratchett's penultimate to date, lacks focus in rather the same way as his more recent and disappointing Snuff. Another book intent on deglamorising magic -- and, much though I love Pratchett, one that seems to me to be in a different league altogether -- is The Magicians by Lev Grossman. This is one which does live up to its hype; The Magicians is a very strong novel in its own right, as well as being both a brilliantly-imagined fantasy and a clever critique of fantasy in general.

Grossman's glittering, crystalline prose is perfectly pitched to serve the clarity of his purpose: in the end, one suspects, the only reason this is a fantasy at all is because the real world it depicts is ultimately equally unsatisfying.

If I had to recommend one of these books, this would be the one.

[Edit 26/5/12: Somehow managed to forget Shada. Have included it now. Also linked Foxe's Book of Martyrs.]

But... But... But... Dune, Phil! *Dune*!

ReplyDeleteTo be fair to your review, a book that I suspect I read at *exactly* the right time (approx 16 years of age). It made a huge impression on me, and while I have never been tempted by the sequels and other spawn of the series, I adored it.

And was unimpressed with the film. The Scify miniseries - now that was good.

I was underwhelmed by Dune too; I've read it a couple of times, the first in my early teens, and again more recently to see if I'd just been too young to properly appreciate it (apparently not). I must get a copy of the film, though!

ReplyDeleteHonestly, the Lynch film was everything I expected or wanted the novel to be. Part of the reason I'd never got round to reading the book was because I suspected it wouldn't live up to the expectations the film created.

ReplyDelete(It's one of his less popular films, mind you, and lots of people don't like it at all. I think it's fantastic -- and a clear visual influence on Babylon 5, among other things.)

I've never seen the miniseries, but I suspect greater fidelity to the book would make it less interesting for me.

Somewhere in one of the many sequels to Dune which I am never going to pick up again (I offloaded my collection to a young cousin of the right age) there is an introduction explaining that it is indeed primarily about sand, and that Herbert was supposed to be writing a magazine article about desertification, the research for which just got a bit out of hand.

ReplyDelete